Preface:

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, the word “vice” is defined as:

‘a moral fault or weakness in someone’s character.’

So then what is morality?

‘a personal or social set of standards for good or bad behaviour and character, or the quality of being right and honest.’

From here I have some questions:

What makes a certain type of behavior ‘good,’ and another ‘bad’?

Who decided that being ‘honest’ and being ‘bad’ are mutually exclusive?

When does a ‘fault’ in character become a ‘weakness’ in character?

If a society is full of morally twisted people, how far do the praxis of ‘vice’ change?

I’m not saying I have the answers to these questions; I am genuinely asking for your opinions here.

But let me get into this . . .

Hedonism:

In philosophy, hedonism is a collection of arguments that view pleasure as something that should be prioritised as a result of pleasure being the highest form of “good” available to us in life.

Psychologically, theories of hedonism argue that all human behaviours are driven by the incessant underlying motivation to maximise pleasure whilst avoiding pain, and in reference to the self-centered philosophical view of egoism, hedonism implies that people are only willing to help others if some form of personal benefit is expected in return.

In each of these views of hedonism, it’s undeniable that pleasure is posited as being something of value, and so consequently, here’s another definition for you.

Axiology:

‘the study of the nature of value and valuation, and of the kinds of things that are valuable.’

When assessing hedonism through the lenses of axiology, pleasure being the foundation of the aforementioned arguments is furthered by the fact that axiological hedonism sees pleasure as being the sole source of intrinsic value.

It implies that things like money and knowledge are valuable to us, but only to the point that they produce pleasure and reduce pain.

Axiological hedonism can be deconstructed into quantitative hedonism, which focuses on the intensity and duration of pleasures, and qualitative hedonism, which argues that the value of pleasure depends on its quality, and even still, these ideological offsets can be offset by the principles of prudential hedonism and ethical hedonism.

Prudential hedonism argues that pleasure and pain are the only factors of well-being, whilst ethical hedonism extrapolates the axiological view of hedonism to questions of morality—arguing that people have a moral obligation to pursue pleasure whilst avoiding pain.

In all these branches of hedonism, it is maintained that pleasure is worth chasing; the points of contention, and difference therefore, are based off the extent to which it should be chased, and its nature: whether pleasure is a need, a want, a luxury, or a necessity.

Pleasure & Pain:

With pleasure being a fundamental part of all forms of hedonism, pain invariably exists—at the bare minimum—as a foil to the presence of pleasure. Depending on what form of hedonism is being applied, opinions regarding the relationship between pleasure and pain will change.

Most hedonists view pain and pleasure as existing on opposite sides of a scale that passes through a point of neutrality (think of a scale from 1-10, but instead, -5 to 5), and this comes as a result of there being varying degrees to which pleasure and pain can be felt.

Despite this, some hedonists would argue against pain and pleasure existing symbiotically, instead arguing that avoiding pain is more important than the production and experience of pleasure.

I made reference to Paul C. Brunson’s application of Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in my initial essay on Substack (Why Friendship Groups Are Destined to Fail), and to expand on the points I made then, the things that Maslow places on the lower rungs of his pyramid are things that help humans avoid pain.

Things like air, food, water, shelter, and sleep, are non-negotiables when it comes to preventing pain, and like most pyramidic systems, these things must be achieved before one can move a step higher in the pursuit of things that would produce happiness—things like friendship, intimacy, status, and freedom.

This, to me, makes it clear that hedonism is best understood—in a contemporary context—in its ethical form, which, to remind you, argues that people have a moral obligation to pursue pleasure whilst avoiding pain.

Quantifying the Abstract:

In my piece that precedes this one—North-West London Doesn’t Exist—I grappled with the difficulties of quantifying the abstract, namely “homeliness” and how it can/can’t be measured, and in this piece, I arrive here again.

Now, some of you may say that pleasure and pain aren’t abstract in the same way that homeliness is, especially because pain and pleasure can produce tangible bodily reactions to things that homeliness can’t, and to that I say:

Fairs,

I hear you . . .

BUTTTTTTTTT

When analysing pleasure and pain from a hedonistic point of view, it is integral you assimilate your views of these things to emulate the hedonist’s view of these things, because otherwise, we’d be having a conversation in which we don’t even agree on the meaning of two crucial components of this school of thought.

Hedonists prefer to look at pleasure and pain as being all-encompassing, meaning that the words “pleasure” and “pain” can be used to describe any type of experience, be it positive or negative.

When assessing pain and pleasure in this way, anything good—which can range from true love and marriage, to wearing your favourite shirt—is a pleasure, and anything bad—which can range from death, to your favourite movie getting taken off of Netflix—is a pain.

This is where this piece takes a turn from the analytical to the theoretical, because if absolutely anything and everything can be summarised—and therefore classified—as being “good” or “bad,” what stops pleasure and pain from being absolutely everything?

In saying that, I mean:

If everything we experience as part of our humanity boils down to pain and pleasure, what stops pain and pleasure from becoming our humanity?

The Pursuit of Happyness:

Contemporary philosophy has revised some of the ideas that were previously made in connection to pleasure and pain, arguing that: instead of pleasure and pain existing as specific bodily sensations—as was most commonly thought—they exist as attitudes of attraction or aversion, which one holds towards a specific object.

Continuing with this perspective, to have an “attitude” is to have ‘a settled way of thinking or feeling about something,’ and so therefore, to have an attitude of attraction is to think of a specific object as something that has the potential to provide pleasure (and vice versa).

This is particularly important as some proponents of hedonism conceptualise the theory through the lens of happiness, rather than through pleasure and pain.

With happiness being abstract, just like pleasure and pain, quantifying its existence is a contentious topic. Most commonly, happiness is viewed as being the balance of pleasure over pain—meaning that if someone experiences more pleasure than pain, then they are happy (and again, vice versa).

Despite this, divergent views of happiness still exist—like those who view happiness as being determined by one’s satisfaction with life. This is where the question of “attitude” rears its head again, as if one has a favourable view of their life, they can describe themselves as being happy regardless of whether they’ve experienced more pain than pleasure.

Well-Being & Eudaimonia:

Defining “well-being” as being what is ultimately “good” for an individual leads to more questions than answers.

What is “good”?

And who decides that?

And aside from that . . .

It can be good for you, but does that necessarily mean that it’s also good for me?

I think we can all agree that the answer is no to that last one, and so it’s from this point that prudential hedonism espouses its core principal of pleasure taking primacy over pain as being the only source of well-being.

This focus on the satisfaction of desire is where this essay will stem from hereforth, but before that, here’s another definition.

Eudaimonia:

‘the condition of human flourishing or of living well […] the highest human good, the only human good that is desirable for its own sake (as an end in itself) rather than for the sake of something else (as a means towards some other end).’

Again, I made reference to this in my essay on Why Friendship Groups Are Destined to Fail, but in short, eudaimonia is the Aristotelian parallel to Maslow’s concept of “self-actualisation”—the process by which an individual reaches their full potential.

Again we arrive at the word “potential,” and so very quickly, join me on this little tangent:

I hate the word “potential” so so much, but I love it at the same time.

No word feels so liberating and yet constraining at the same time, and so I will be writing a piece about this soon, but ANYWAYYYY . . .

Theories born out of the foundational basis of eudaimonia are often similar to the overarching ideas connected to hedonism. They differ however, based on the former’s emphasis on virtue and self-realisation.

The Paradox of Hedonism & the Hedonic Treadmill:

Hedonism’s focus on the pursuit of pleasure often means that hedonists feel the need to actively pursue their pleasure, but this is where the paradox of hedonism reveals itself.

The theory views the direct pursuit of pleasure as being counter-productive, something that detracts from one’s overall happiness as a result of it becoming a obstacle to it.

To some, the most effective way of producing pleasure is by allowing it to arrive as a by-product of one’s organic endeavors, rather than it having been outlined as the conscious goal/aim of one’s actions. For example, a musician is likely to feel more pleasure when they focus on playing their instrument to the best of their ability, rather than playing their instrument as a means to gain pleasure and/or happiness.

To others, the long-term pursuit of pleasure is essentially futile, as humans tend to have their happiness equalise to a level of stability at some point—no matter the magnitude of a positive/negative change. This implies that an individual’s happiness is bound to be affected by good/bad events, but only temporarily, as the individual is likely to (eventually) grow used to their changed situation.

For example, a newly-married couple might experience another “honeymoon phase” in the months immediately following their wedding, but both parties are likely to grow used to married life at some point in the not-so-distant future, and so this results in the post-wedding high slowly being brought back down to the level the couple were at prior to engaging in matrimony.

This theory, known as the “hedonic treadmill,” undermines one’s desire to actively engage with things that could lead to increased happiness in the long-term, given that once the individual reaches said point of increased happiness, they’re likely to underrate it once it becomes present and not just something that glistens in the future.

This effect explains much of society’s lack of urgency when it comes to dealing with issues that aren’t seen as being detrimental right now, and on an individual level, this effect explains why people are so okay with chasing fleeting spikes in happiness in the form of immediate gratification.

Gratification:

Gratification—the pleasurable emotional reaction that comes as a result of fulfilling a goal/desire—acts, like all emotions, as a motivator of behaviour, and therefore, it plays a crucial role in the make-up of humanity’s social systems.

Walter Mischel—an Austrian-American psychologist—who specialised in personality theory and social psychology, performed an experiment on four-year olds in the late ‘60’s to test their patterns of gratification in a test known as the “marshmallow experiment.”

In this, Mischel examined the processes and mental mechanisms that allow for a young child to be able to reject immediate gratification in favour of delayed gratification, by giving the children the option of receiving one marshmallow immediately, or waiting ten minutes before receiving two.

The focus here isn’t on the treat itself (the marshmallow could be substituted for any other desirable treat), but more on the fact that when Mischel followed up on the children some years later, he found a startling correlation between those who succumbed to immediate gratification, and their outcomes in life.

The children who had difficulty with delaying gratification tended to have higher rates of obesity and sub-par levels of academic achievement when compared to their counterparts, which is cool . . . I guess . . . but I’m more concerned with the fact that children who were raised by parents who lived just below the poverty line were much more likely to fold under the pressure of potentially immediate pleasure in comparison to the children whose parents were college-educated.

This brings me back to the earlier point of satisfying desire, and leads me to believe that people who are more likely to experience pain, are also more likely to want to experience pleasure—thus explaining the difference in results based on economic backgrounds.

Desperation:

Talking in regards to modernity, and where we are now as a society, people seek pleasure consistently as a result of living in constant pain.

Different people experience different pains differently, and so I’m not going to waste your time by explaining how or why people are suffering right now (I already wrote a piece on this called How Suffering Won the Lottery of Life), just think of how/why you are suffering instead, because in the end, it is all the same:

We want to feel good whenever we feel bad.

Again:

If absolutely anything and everything can be summarised—and therefore classified—as being “good” or “bad,” what stops pleasure and pain from being absolutely everything?

In saying that, I mean:

If everything we experience as part of our humanity boils down to pain and pleasure, what stops pain and pleasure from becoming our humanity?

Nothing does.

And that explains A LOT.

That explains why almost everything we see on social media is so polarising nowadays; pretty much all forms of content—regardless of their niche—feels as though it’s been made with the intention of actively recruiting people to feel the same pleasure/pain that the creator feels, and this exists as a snapshot of why each side of any (seemingly) binary debate seems to be drifting further and further away from each other:

Immediate gratification has never been needed so immediately.

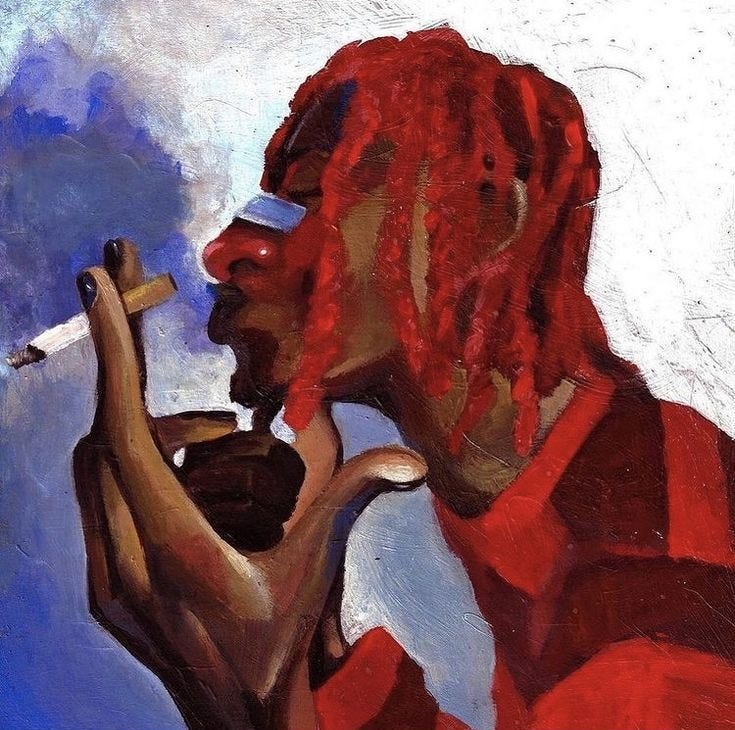

People are DESPERATE in ways we couldn’t even conceive of not so long ago, and this is why relapse is so easy nowadays. Forget all the different types of vices that people like to leech pleasure from—the essence is all the same—people have grown accustomed to having to steal their pleasures in the same way that pain steals their sanity.

Being constantly reminded of your pain whilst others bask in their pleasure is a catalyst for relapse in a way it has never been before.

Why?

Because pleasure has never been as inaccessible as it is now.

“Fine” is the New “Good”:

Being able to extract pleasure from something doesn’t necessarily equate to that something being “good” for the individual in a well-being sense, it just means it isn’t painful.

Earlier, I spoke on imagining the scale of pain and pleasure as going from -5 to 5, passing through a point of neutrality (that being zero). Now, I feel justified enough to be able to say that, at the bare minimum, at least one of these following two statements are true.

Either:

the -5 to 5 scale has shifted downwards, meaning it’s more like a -7 to 3 scale now, with the overall amount of “good” or “pleasure” one can feel having decreased,

OR

feeling “good” now doesn’t feel as good as it used to (and vice versa), meaning that humanity’s total emotional bandwidth has decreased overall.

In either statement, one thing is true.

Humanity has lost some part of itself, and THAT is why people engage with the vices that they do.

Axiological hedonism would cry if it could see us right now.

The intensity, quality, and duration of our pleasures have all decreased, to the point that I could argue that instead of zero being the point of neutrality on this revised -7 to 3 scale—meaning that we supposedly have more “bad” and “pain” available to us than “good” and “pleasure”—the point of neutrality just . . . isn’t that neutral anymore.

Everyone seems to be operating from a place of lack.

Whether it’s a lack of love, laughter, sex or sleep, it seems to me like -2 is the new zero; doing “fine” is the new doing “good,” and that “good” was never THAT good in the first place anyway, and so GENUINELY what the fuck are we doing by being just “fine?”

Getting high as fuck, spamming orgasms and drinking cheap wine . . .

That’s my guess at least.

“This effect explains much of society’s lack of urgency when it comes to dealing with issues that aren’t seen as being detrimental right now…”

i hadn’t really thought of if in this way before. maybe, to some extent, our inability to get an environmental movement properly off the ground is because things are “good enough” as they are now. there is some kind of collective acceptance of the status quo based on an intrinsic quality in regards to pleasure-based motivation. it can be so frustrating to see people not mobilize to get something done, but we are very much a species which adapts as things come (in reality, most, if not all are the same) as opposed to excessive planning.

So much to unpack in this piece, so many concepts in one!! J’adore!!